My experience: Not Child’s Play – a family taken hostage

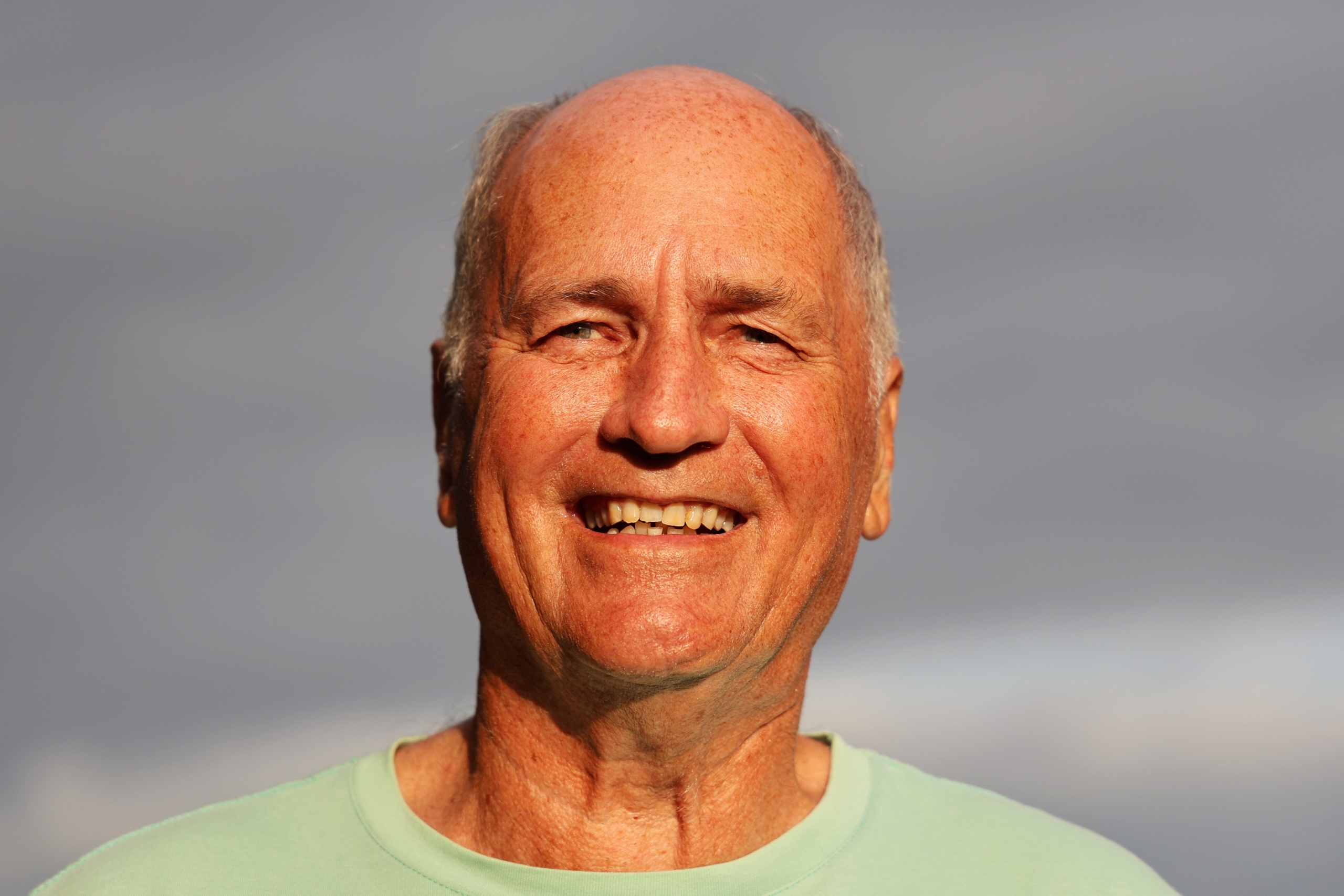

A labour of love saw Dave Muller spending ten years building a yacht from scratch and in 1990 he set off with his family to fulfil his dream of voyaging to the tropics. Despite years of sailing expertise, they ran aground off Mozambique and were quickly seen by local resistance soldiers who took them hostage and held them in the jungle for seven weeks.

Dave first contacted Hostage International more than thirty years after their ordeal, unsure as to whether this was a ‘normal’ hostage experience. Here he reflects on how he, his wife Sandy, and two children Tammy and Seth, who were eight and five at the time, have been affected by their ordeal.

My family, Sandy my wife, and our children eight-year-old Tammy, and five-year-old Seth, were sailing from our home in East London in South Africa to the tropical Bazaruto Islands in Mozambique. Before leaving, we knew of the civil war in Mozambique but had been assured that the beautiful coastline was safe and ‘secure’. I had taken time off from my work as an architect for us all to gain experience in longer voyages while giving Sandy, a malacologist (someone who studies molluscs) the chance to do her research into marine life.

Our plans came to a sudden end when Arwen, our yacht, ran aground in the middle of the night just kilometres south of the islands. It happened to be Seth’s fifth birthday so we held an impromptu birthday party for him while we waited for the tide to return to refloat Arwen. However, our party was gate-crashed (about five minutes after I’d taken the photograph below) by some boy soldiers and from that moment our lives dramatically changed.

Why were we taken?

Although at the time we did not know the reason, we later discovered that Renamo resistance soldiers had held us hostage in retaliation for South Africa, our home country, withdrawing support from them. Both Renamo and Frelimo knew the civil war could not continue indefinitely and peace negotiations were inevitable. Each therefore wanted to place themselves in the strongest possible position once the details for the peace were negotiated. Renamo hoped to force South Africa to renew their support. However, the reality was that in 1989 the world changed with the fall of the Berlin wall and the end of the Cold War. Renamo was losing the propaganda war; the ANC had been unbanned and Nelson Mandela was a free man. There was no chance of South Africa renewing their support. Frelimo knew this and knew that if we were killed, regardless of who had actually done the killing, blame would fall on Renamo.

So that is how we ended up in the terrifying and bizarre position whereby our captors, Renamo, were forced to protect us from harm and death. A bounty had been placed on our heads by Frelimo who intensified their attacks on the camp were we were held.

Sharing my story

When asked to share my story here to help highlight the need for the work of Hostage International and the experiences that people live through, I was keen and thought it would be no problem. However, the relevant words to describe the flood of emotions linked with being taken hostage has not been easy. Despite my having written a book, Not Child’s Play, about the strange and unexpected events we experienced, here I wanted to delve into elements not included in my book; how fundamentally life changed for us the moment we realised those children facing us on the beach were child soldiers pointing AK-47’s at my family.

Not Child’s Play is written from diaries that I kept throughout our ordeal. I felt an overwhelming need to tell my story of our horrifying and terrifying time in captivity. The extraordinary situation into which we were thrust – being held by child soldiers while desperately attempting to survive and keeping some semblance of normality for our own children.

After our release and rescue, we were fortunate to receive expert help from a team of councillors of the South African Defence force medical corps. They had anticipated we would be suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. We had never heard of ‘PTSD’, so it came as a shock in the days following our rescue, as we were gently taken through the process of a physiological debriefing, to discover just how damaged we were. Our carers asked us to tell the story of what had happened. It was not long before we hit a wall as we came to the first traumatic event and found we simply could not speak the words. It felt as though our brains refused to let us voice what had happened. We were gently guided past this event and others that emerged. Never could I have anticipated the power of the mind to suppress bad thoughts and even physically take control of one’s body.

However, I have found that the years do heal and soften the memories, and today, while I feel close to being my old self, I know this is not totally true. I lost something and it is this “lost something” that is so difficult for me, and I suspect many other former hostages, to share.

What was lost?

I feel that I lost an innocence. 34 years after the event I still cannot come to terms with the callous brutality of the boys who killed people in such a cold, calculated manner. Worst of all, I have to confront the fact that our presence resulted in an escalation of fighting, and because of this, the killing of many innocent people. It makes me feel tainted by a knowledge that is so real I do not even want to place it in words.

My self-perception as Dave, the yachtsman and traveller, husband, father, a man charting his own destiny, was lost. The same for Sandy. Once back home we had to fiercely recreate ourselves and build a new identity. One based on survival, self-reliance and a refusal to succumb to any feelings of victimhood. This has made us self-contained, but brittle, and as a result, emotionally harder that we often would like to have been.

A belief that simply having a “strong faith”, as found in religious observance was enough to carry one through or avoid experiencing trials in this life. I found it difficult to come to terms with the different ways in which my Christian friends viewed “faith” and the act of prayer. It seemed so different from that which I experienced. They wanted me to be joyful and praising God while I was dealing with deeply spiritual questions such as “why”, and the reality of evil existing alongside good, while all I wanted was to quietly ponder upon God’s saving grace. Thankfully, most of us do not suddenly find ourselves confronting demons and the concomitant testing of our faith. We overcame, and as a result our faith has strengthened. However, that self-awareness of becoming a “survivor” makes me feel like an “outsider”, even amongst my fellow Christians.

I do sense that some element of optimism has been lost from my worldview. It is difficult not to live with an awareness that at any moment some devastating life-changing event could occur. If it has happened before, why not again. Exposure to world news only reinforces this unease as we invariably witness people whose lives are changed when they become hostage to the circumstances surrounding them. This unease is not to be confused with fear. It is rather a sadness that there is an inexplicable flaw in our existence. It is as if the song of my life has lost the chorus that would otherwise have linked the verses into a melody.

What was gained?

The losses I mention must not be over-stated as much was also gained from those deeply disturbing experiences. Not least an appreciation for the many things we take for granted such as living under a stable government; opportunities for undertaking worthwhile work; freedom to travel.

For me I gained a deep sense of compassion for all humanity. Horrific as were the actions of the boys, they simply knew no better. It is comforting to know that with support many of those boys did grow up and become exemplary citizens and parents.

Despite exposure to the brutal realities of war, I know goodness and hope predominate. Hostage International is an example of this as they reach out to help the hurt and perplexed.

Regrets?

I have regrets. As former hostages or wrongfully detained, I suspect we are poor at self-diagnosing ourselves. I certainly was.

After our release, in our own need for self-preservation, we had become oblivious to the feelings of others and did not realise they too had suffered. We thought we were behaving normally, when in fact the endless battle to survive, to never lose hope, to protect our two children and remain mentally strong, had blinded us to our fragile mental state. Even after our rescue, our desperate attempts to try to turn our upside-down lives back to some semblance of normality made us oblivious to the pain with which our families and many friends were still struggling. To this day my sister cannot bring herself to read my book. Nor could my mother. Only recently, has Tammy read the book and she says it was a real struggle because it exposed so much she had not known. This aspect of our blindness to the hurt and trauma experienced by those who love us, is one where Hostage International, had they existed at the time, would have been a great help and thankfully now are.

We cannot always find the words to express our feelings, which is why we need poets. Robert Frost so succinctly expresses my feelings in these words from the first verse of “A Leaf Treader”:

I have been treading on leaves all day until I am autumn-tired.

God knows all the color and form of leaves I have trodden on and mired.

Perhaps I have put forth too much strength and been too fierce from fear.

I have safely trodden underfoot the leaves of another year.

Autumn-tired. Trodden on and mired. Been too fierce from fear, say it all. Horrible things do happen, but also wonderful things, and it is in these we rejoice as we tread underfoot the leaves of another year.

Not Child’s Play

Dave is generously donating all proceeds from sales of his book Not Child’s Play to Hostage International. He explained:

“We were incredibly fortunate to survive our time as hostages and owe our lives to many who worked tirelessly to secure our release. As more details of the negotiations and events that ultimately lead to our release have become known, I’ve realised the story of Not Child’s Play is not my story. It belongs to those who made it possible for me to tell the story. This is why, after chatting with my family, we are happy to donate any proceeds from the sale of the book to Hostage International. It is our way of saying thank you to those worked to save us and acknowledging the crucial, but often unperceived, work of Hostage International.”

Not Child’s Play is available as an eBook on the following sites:

Audiobook web sites:

January 2025