My experience: Kidnapped in Somalia

Colin Freeman, journalist and former foreign correspondent at the Sunday Telegraph, highlights how Hostage International supported his loved ones when he was kidnapped in 2008

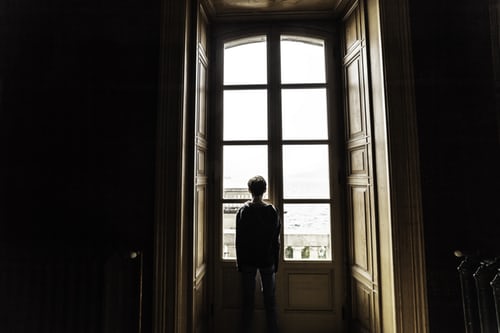

One November afternoon back in 2008, my Dad got a phone call from my editor at the foreign desk of the Sunday Telegraph. They had bad news. I’d been on assignment in Somalia, reporting on the country’s emerging piracy crisis, and hadn’t been heard from for several hours. It wasn’t quite clear yet what had happened, but the word from the ground was that I’d been kidnapped along with my photographer. My boss wanted my family to hear it from him first rather than learning about it on the news. Dad listened as best he could, then went through to the kitchen to break the news to Mum. Amid the shock, one thought kept going round in his head:

“Something that only happens to other people has just happened to us.”

Every family faces life-threatening crises at some point, but normally, it’s something that falls into the realm of the familiar, like a road accident, or a serious illness. Kidnappings – unless you live in somewhere like Iraq or Mexico – lie beyond that. Most people will never experience one, or know anybody who has. It follows, therefore, that when you get a phone call like my Dad did, you think: “What on earth do we do now?”

Here in Britain, people turn to the Foreign Office, the police – and, if the hostage, like me, was kidnapped while working – an employer. They’re the ones who normally assume the lead for trying to resolve things, be it liaising with authorities overseas, or negotiating with kidnappers to secure a hostage’s release.

However, one thing the police, Foreign Office or an employer will generally not do is give families a running commentary on what is actually being done to get the hostage freed. Some information will be shared, but usually the bare minimum, and often only after the fact. The day after my Dad got that phone call, the family were invited into The Telegraph offices, along with my partner, Jane, and introduced personally to the “crisis team” that would be handling things. The Foreign Office also appointed a family liaison officer.

From then on, there would be daily phone calls with updates on the situation. But these calls felt like a carefully-controlled trickle of information. They learned that we were being held in a cave in some mountains, and that we were being fed on goat meat and rice. They learned that the gang holding us had not hurt us, but were demanding a ransom to set us free. And – in a titbit presumably designed to keep their spirits up – they learned that that I’d joked that the cave was in a very picturesque spot.

What they didn’t learn was any detail of the negotiations that were ongoing to try to free us, beyond a general reassurance of “trust us, we are doing everything we possibly can.” And that, for most hostages’ families, is one of the toughest things to cope with of all. After all, when your loved one’s life is hanging in the balance, it’s hard to “trust” anyone – let alone people who won’t tell you what they’re actually doing, and who request that you simply take them at their word.

Being kept in the dark:

The reasons for this information blackout are usually well-intentioned. For one thing, hostage negotiators like to keep their tactics confidential, to give them the maximum possible edge over the kidnappers. For another, it reduces the risk of sensitive discussions leaking into the public domain, which can complicate negotiations. And for a third, much as families may find it hard being kept in the dark, ignorance can also be… well, not bliss, but better than knowing the full picture.

Hostage negotiations can often be difficult, with threats being made, bluffs having to be called, and tough decisions required. For most families, I suspect, being involved in day-to-day would create an intolerable burden of additional stress. In my own case, for example, there was a weekend when the kidnappers threatened to beat us up, and then had a gunfight with a rival gang. With hindsight, Jane says she’s glad she didn’t know about it at the time. Apart from anything else, there was nothing much that she or anyone else could do about it.

Still, that was with hindsight. At the time, both Jane and the rest of my family found it hard to put blind faith in those tasked with getting me out, and as the weeks passed, they couldn’t help entertaining doubts. What if the information blackout was just the excuse for some sort of cover-up? They didn’t know much about Somalia, beyond the fact that it could be a lawless and dangerous place. It’s easy to see why their imaginations ran riot. Might I, as a reporter, have stumbled on some top secret scandal that meant I had to be silenced? Or might there already have been aa rescue attempt that had gone wrong, with nobody wanting to admit it? Or might those Foreign Office mandarins just not be making enough effort?

It sounds like conspiracy theory stuff, or the plot of a bad airport thriller. But when someone you know has unexpectedly vanished into thin air, the plot of a bad airport thriller is exactly where you feel you are. Conspiracy theories suddenly seem more plausible. And where do you turn to for independent advice? It’s not as if every high street has a hostage negotiator who can offer a second opinion.

Support from Hostage International:

This, luckily, is where Hostage International comes in. The charity does not get involved in the specifics of individual cases, but it does offer independent, general support on a confidential basis, so that families aren’t dependent purely on the Foreign Office, police or an employer. In my own case, Hostage International put Jane in touch with one of their volunteer supporters, to whom she related the steps that had been taken in my case thus far. To her immense relief, the volunteer said that it sounded like things were being done more or less according to the book. It might not seem like much, but at the time, the mere confirmation that the correct procedures were being followed was a very welcome reassurance.

The charity also put Jane in touch with a counsellor who specialised in hostage cases. Among the advice the counsellor gave was to keep a diary. The diary helped Jane to take things one day at a time, and, at the end of the tougher days, to psychologically turn the page and start anew. Quite often, those tougher days were nothing to do with what was happening to me in Somalia, but prompted by day-to-day life at home – which for hostages’ next of kin, can often bring unexpected challenges.

For one, they’re often asked not to tell anyone other than very close friends about what has happened, in effect having to present a normal front to the outside world. Jane, for example, simply told people at work that there was an unspecified “family crisis”. But even that didn’t feel like it did justice to the turmoil going on inside her head.

There can also be humdrum bureaucratic issues that arise when someone’s life gets suddenly put on hold: summons for unpaid bills, for example, or bank cards that need to be cancelled. When your loved one’s life is on the line, the last thing you want is to be stuck on hold to some call centre, asking them to deal with you even though you’re not the “account holder”. Hostage International can offer help with these kind of obstacles, and also assists families in accessing medical and legal services. Crucially, the charity’s networks of volunteers also include people who have been through a hostage trauma themselves – who, for some of those tougher moments, are perhaps the only souls who can really understand what it’s like.

On which note, in writing this piece, I wouldn’t claim to speak for the experience of every hostage, much less their families and loved ones. Every kidnapping is different, with its own particular challenges. And if anyone is reading this with a loved one currently in captivity, I should be honest and point out that my own kidnapping probably falls at the lesser end of the spectrum.

For one thing, I wasn’t harmed. And for another, I was only held for six weeks – which, compared to what some hostages endure, is not that long. To put it in perspective, I’ve just finished writing a book about three ship’s crews who spent more than three years as prisoners of Somali pirates, compared to which my experience seems like small beer. Plus, as a journalist covering Africa and the Middle East, I was in a line of work where kidnapping is something of an occupational hazard, which meant I knew a little about what to expect, and how to cope with it. That didn’t make it any easier for Jane, my Dad and my other loved ones back home – who, as in every kidnapping, are the real targets anyway. Which, ultimately, is what makes Hostage International’s work all the more important.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE OUR WORK BY DONATING HERE

Colin Freeman is a London-based journalist and author. His account of his own abduction, Kidnapped: Life as a Somali pirate hostage, is published by Monday Books. His latest book, Between theDevil and the Deep Blue Sea, the mission to rescue the hostages the world forgot, will be published by Icon Books on March 11.

Five former hostages in one room: Colin pictured alongside Ingrid Betancourt, Terry Waite CBE, John McCarthy CBE and Judith Tebbutt at an event organised by EdmissionUK with Hostage International in 2019. Read the original story here.

About Hostage International – We have a network of volunteer caseworkers, many with direct experience of being held hostage or having had a loved one kidnapped. We also have a network of experts including psychologists, psychiatrists, lawyers, financial advisors and media experts with in-depth understanding of the effects of this niche and terrifying crime. Find out more about our services.

2 March 2021